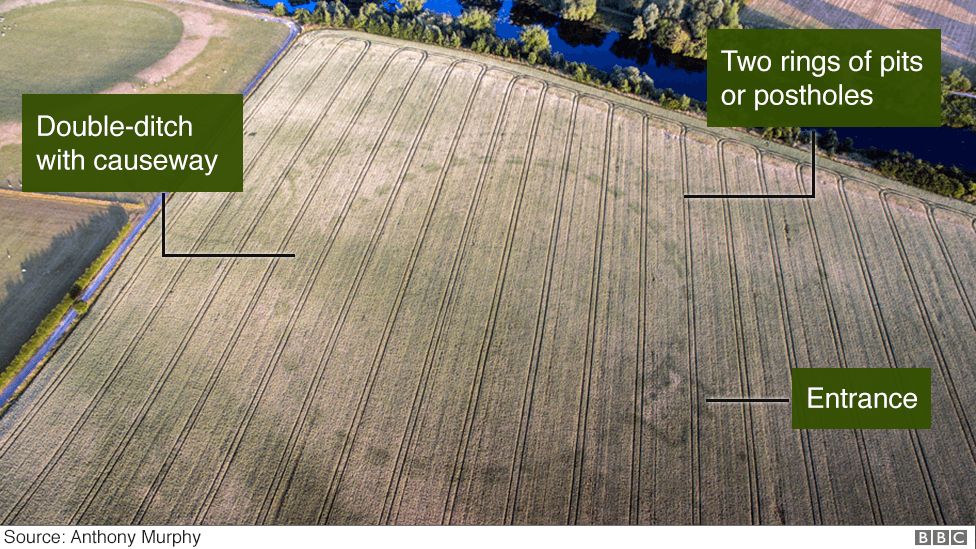

The archaeological site. Photo/Ragnheiður Traustadóttir

A team of Icelandic archaeologists has discovered occupation layers, dating back to the settlement of Iceland in the ninth century until the beginning of the 14th century, on Mosfell hill in Mosfellsdalur valley, just east of Reykjavík. The discovery is believed to be able to shed light on the history of the Middle Ages in the area.

Work on a new parking lot by Mosfellskirkja church was halted by the Cultural Heritage Agency of Iceland in April, and subsequent archaeological research revealed the layers. The agency decides this week whether excavations are to be continued. Only part of the site was damaged when work on the parking lot was in progress, according to archaeologist Ragnheiður Traustadóttir. The site seems to have been affected more in 1960, when a minister’s residence was built on the lot. Two areas are under investigation, one north of road leading up to the church, and the other east of the current parking lot.

Read the rest of this article...